New York Tax Planning for CPAs – State Rules, Risks & Strategy

[Last Updated on 3 days ago]

TL;DR — New York Tax Planning for CPAs

- New York tax planning requires a state-first analysis because federal tax treatment does not reliably translate to New York outcomes.

- CPAs must navigate independent New York rules governing residency, nexus, income sourcing, and entity-level taxation.

- Key planning drivers include New York personal income tax, corporate franchise tax, and sales tax, each operating under separate standards.

- The New York PTET functions as a SALT-focused planning mechanism, shifting certain state tax payments to the entity level.

- PTET benefits depend on eligibility, ownership structure, timing, and coordination with owner-level filings.

- Most New York tax planning issues arise from misinterpreting state-specific rules, not from calculation errors.

- AI tax tools support New York tax planning by helping CPAs research state-specific rules and maintain consistency, while professional judgment and compliance decisions remain with the CPA.

Have you ever wondered why New York tax planning requires a fundamentally different approach from CPAs compared to most other states?

New York tax planning operates within one of the most complex and high-burden state tax environments in the United States due to

- Layered taxing authorities,

- Aggressive enforcement standards, and

- Elevated marginal rates.

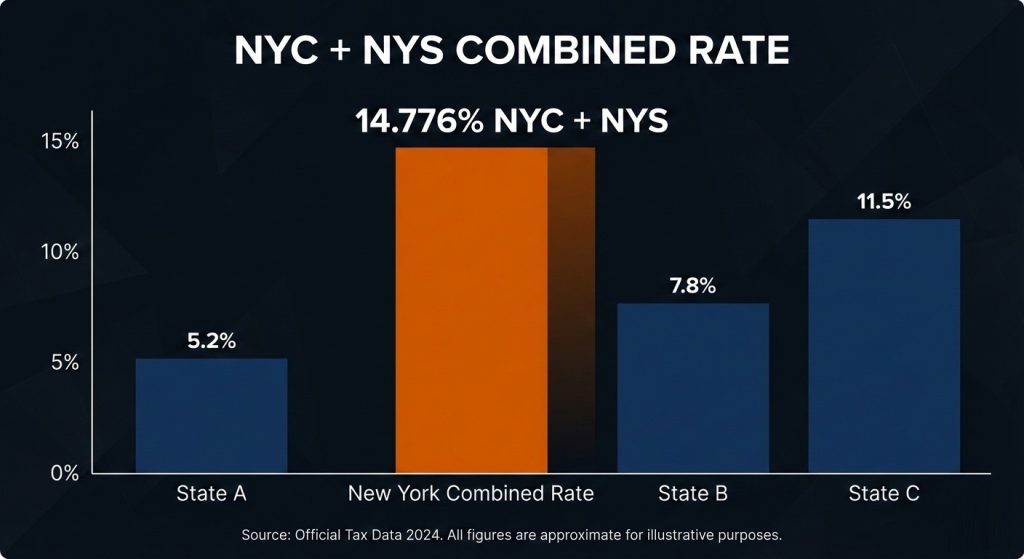

New York State imposes a top personal income tax rate of 10.9%, and New York City adds a local income tax of up to 3.876%, resulting in a combined top marginal rate of 14.776% for high-income taxpayers subject to both state and city taxation (Source).

These rates place New York among the highest-taxed jurisdictions nationwide and materially influence planning decisions for individuals, pass-through owners, and closely held businesses.

For CPAs, effective New York tax planning extends well beyond federal conformity adjustments or year-end deductions.

It requires

- Structured Evaluation of Residency Standards,

- Nexus Exposure,

- Apportionment Formulas,

- Sales Tax Sourcing, and

- Entity-Level Elections, Such As The New York Pass-Through Entity Tax.

As client profiles and filing positions become more complex, New York tax planning for CPAs increasingly depends on organized research workflows and consistent interpretation of state-specific rules rather than manual recall alone.

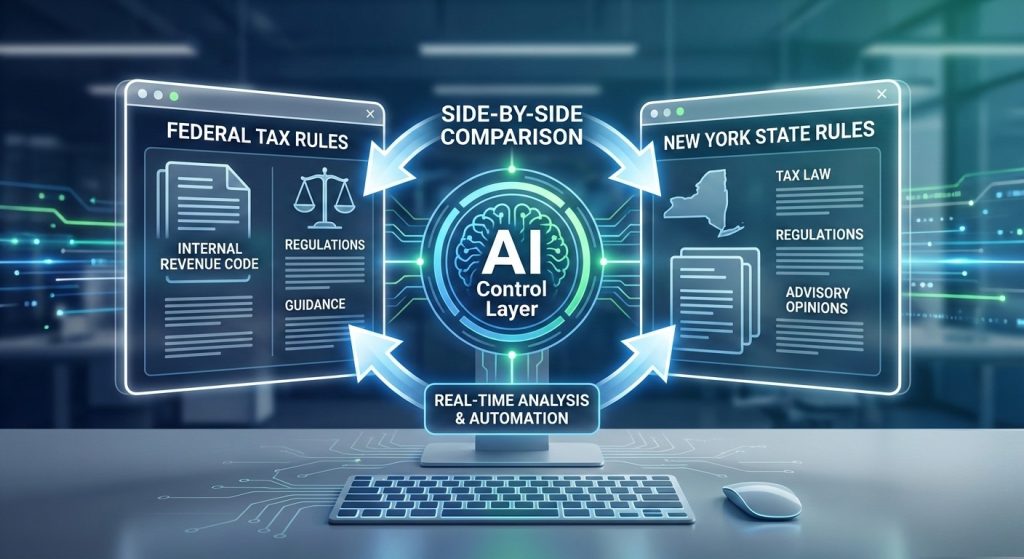

CPA Pilot supports this process by helping tax professionals:

- Research New York–specific tax rules across complex state and local regimes

- Surface relevant state and federal tax guidance for side-by-side comparison

- Organize tax planning considerations across varied fact patterns and client profiles

- Improve consistency and efficiency in New York tax research workflows

- Preserve professional judgment, compliance decisions, and client responsibility with the CPA

The next section explains why New York tax planning demands a CPA-specific framework, beginning with how New York’s structure differs from federal tax planning and why those differences increase compliance and audit risk.

Table of Contents

- Why New York Tax Planning Requires a CPA-Specific Framework for Compliance and Risk Control?

- Core New York State Taxes That Drive CPA Planning Decisions

- Pass-Through Entity and SALT-Focused Tax Planning in New York

- New York Residency and Domicile Rules Affecting Individual Tax Planning

- Multistate and Nexus Considerations for New York Tax Planning

- New York Tax Compliance Timelines and Risk Areas CPAs Monitor

- How AI-Assisted Research Supports New York Tax Planning Workflows?

- Frequently Asked Questions on New York Tax Planning

Why New York Tax Planning Requires a CPA-Specific Framework for Compliance and Risk Control?

New York tax planning requires a CPA-specific framework because the state applies its own definitions, tests, and sourcing rules that do not reliably align with federal tax concepts.

Unlike states that largely conform to federal tax treatment, New York frequently departs in how it defines:

- Residency,

- Sources Income,

- Applies Nexus Thresholds, and

- Evaluates Entity-Level Elections.

This means CPAs cannot safely rely on federal outcomes as a proxy for New York tax exposure.

Comparable complexity exists in other high-regulation states, such as California, where California tax planning also requires independent residency, sourcing, and compliance analysis separate from federal tax treatment.

From a practical standpoint, New York tax planning becomes a rule-layering exercise, not a single calculation.

CPAs must evaluate how state statutes, administrative guidance, and audit positions interact across personal income tax, corporate franchise tax, and sales tax—often for the same client in the same year.

This is why New York planning decisions must be documented, researched, and reviewed independently rather than inferred from federal results.

How do New York Tax Rules Differ From Federal Tax Treatment?

New York introduces planning risk when CPAs assume federal alignment in areas such as:

- Residency determinations: Federal filing status does not resolve New York residency, which relies on domicile factors and statutory residency tests (permanent place of abode plus day-count thresholds) rather than federal residency concepts.

- Income sourcing rules: Compensation, pass-through income, and business receipts may be sourced differently at the New York level, especially for remote workers and multi-state businesses.

- Nexus thresholds and economic presence standards: Federal tax law does not establish nexus thresholds for state taxation. New York applies its own nexus standards based on physical presence, economic activity, and sales thresholds, which can trigger income tax, franchise tax, or sales tax obligations even when no federal nexus exists.

- Entity-level elections: New York-specific elections—such as pass-through entity tax participation—create outcomes that do not exist at the federal level and must be evaluated separately.

Because these rules are enforced independently, New York planning errors often arise not from miscalculation, but from misinterpretation or missed state-specific requirements.

Common PTET Errors CPAs Encounter in New York

In practice, CPAs most often encounter the following errors:

- Assuming federal treatment controls New York outcomes: Applying federal residency, sourcing, or entity treatment without validating New York–specific rules.

- Treating the PTET election as automatic or universally beneficial: Making the election without evaluating ownership composition, eligibility, or SALT interaction.

- Missing nexus created by economic or remote activity: Overlooking the New York nexus triggered by sales thresholds or remote employees, even when no physical presence exists.

- Incorrect income sourcing at the entity or owner level: Relying on federal sourcing logic instead of New York’s receipts-based and activity-based sourcing standards.

- Failing to coordinate entity-level payments with owner-level credits: Creating mismatches between PTET payments, owner credits, and estimated tax planning.

- Overlooking New York-specific election timing or filing deadlines: Missing deadlines that affect credit availability and downstream reporting.

- Assuming sales tax exposure mirrors income tax exposure: Ignoring that sales tax obligations may arise independently of PTET or income tax analysis.

- Insufficient documentation for audit-sensitive positions: Lacking clear support for elections, allocations, or eligibility determinations.

These issues reinforce why PTET analysis must be handled as a distinct planning layer, coordinated carefully with SALT considerations and owner-level reporting, rather than treated as a mechanical add-on to pass-through compliance.

Now that the need for a CPA-specific framework is clear, the next section breaks down the core New York taxes that most directly shape planning decisions and compliance risk.

Core New York State Taxes That Drive CPA Planning Decisions

New York tax planning begins by identifying which state-level tax regimes apply to a client’s activities, entities, and income streams.

Unlike states with narrow tax exposure, New York imposes multiple taxes that operate independently, each with its own base, thresholds, and compliance risks.

For CPAs, planning accuracy depends on understanding how these taxes intersect rather than evaluating them in isolation.

The three tax categories that most often drive planning decisions are:

- New York State personal income tax,

- New York corporate franchise tax, and

- New York sales tax.

Each tax introduces different sourcing rules, nexus standards, and audit considerations that affect planning outcomes across individuals and businesses.

Let’s explore each of them in detail

- New York State Income Tax and Owner-Level Exposure

New York State income tax directly impacts individuals, partners, and shareholders based on residency status and income sourcing.

Planning challenges often arise when income is earned across state lines or allocated through pass-through entities.

CPAs must evaluate whether income is taxable as resident income, nonresident New York–source income, or partially allocated based on activity within the state.

Example: A partner in a multi-state partnership reports income federally without state-level sourcing detail. At the New York level, that same income may require allocation based on New York activity, changing the effective tax exposure for the individual partner.

- New York Corporate Franchise Tax and Entity Structure

The New York corporate franchise tax applies to corporations and certain pass-through entities based on business presence and receipts. The tax base can vary depending on

- Entity classification,

- Income apportionment, and

- Filing status.

All-in-all, New York uses receipts-based sourcing and apportionment rules that differ from federal income attribution.

CPAs must evaluate how business receipts are sourced to New York and how those receipts affect franchise tax liability, even when a business operates primarily outside the state.

- New York Sales Tax and Transaction-Level Risk

New York sales tax planning becomes critical when businesses sell taxable goods or services into the state, including through remote or digital channels. Sales tax exposure often arises independently of income tax obligations.

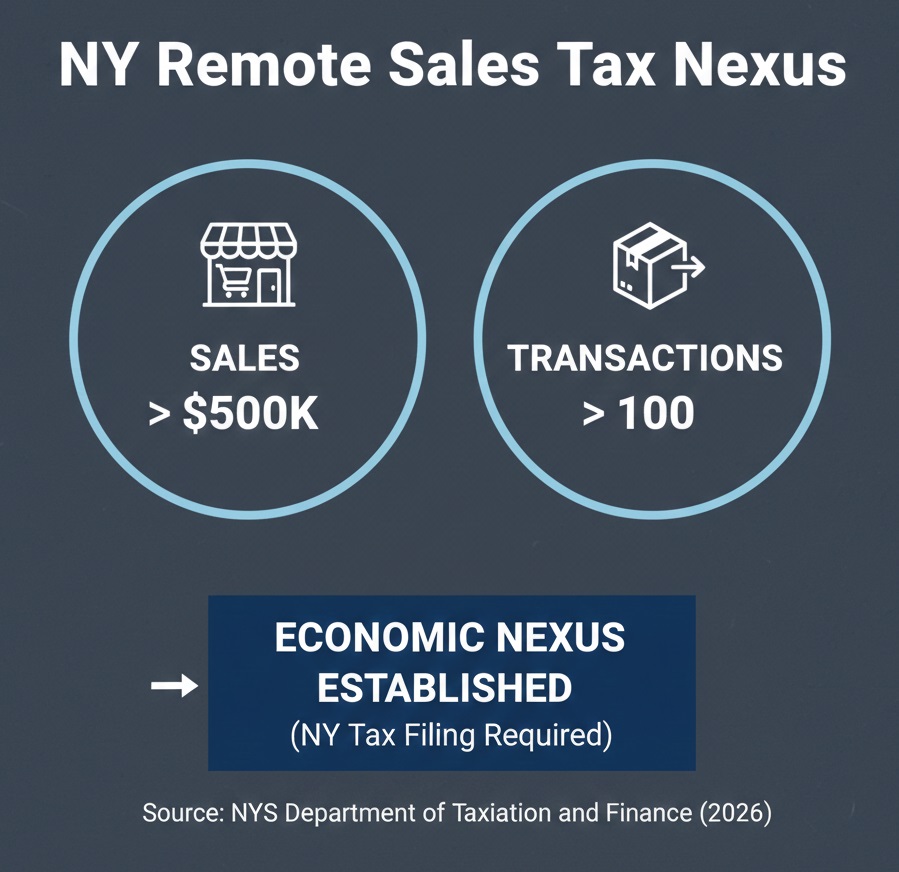

Basically, New York enforces economic nexus standards for sales tax that require registration and collection once a remote seller exceeds both $500,000 of taxable and exempt sales of tangible personal property delivered into New York and 100 separate transactions into the state during the preceding four sales tax quarters.

New York’s economic nexus thresholds for sales tax registration are defined by the New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, and apply independently of income tax nexus standards.

CPAs must assess transaction volume, customer location, and product taxability to identify exposure early.

Once these core New York taxes are identified, planning decisions often shift to entity-level strategies, including how pass-through structures and state-specific elections affect owner outcomes.

Pass-Through Entity and SALT-Focused Tax Planning in New York

New York’s pass-through entity tax (PTET) and its interaction with the federal state and local tax (SALT) deduction limit introduce a distinct planning layer that operates independently from

- Income sourcing,

- Nexus, or

- Residency analysis.

This layer focuses on where deductions are realized, how tax payments are structured, and which level of taxation absorbs state tax costs.

For CPAs, this means PTET planning and SALT-focused planning must be evaluated together, but not conflated with earlier state tax determinations.

PTET as a SALT-Focused Planning Mechanism

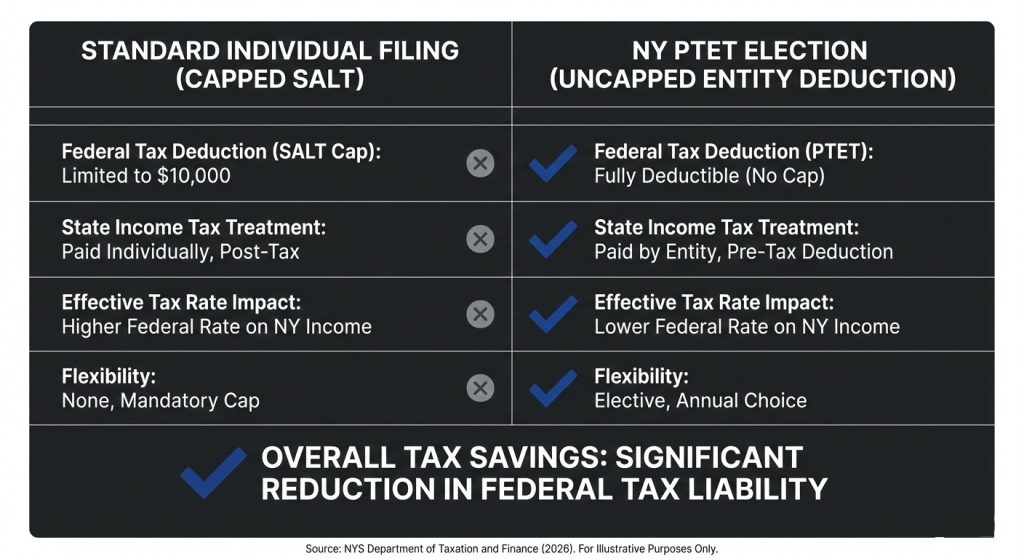

New York’s PTET exists primarily to address the federal $10,000 SALT deduction limitation by shifting certain state tax payments from the individual level to the entity level.

This creates planning considerations that are not present in standard pass-through taxation:

- Deduction location shift: State taxes paid at the entity level may be deducted by the entity for federal purposes, rather than being limited at the owner level.

- Owner-level credit coordination: Owners receive a New York PTET credit, which must be coordinated with individual state filings without duplicating or disallowing benefits.

- Federal–state interaction risk: The federal treatment of entity-level deductions and state-level credits requires alignment to avoid mismatches between federal deductions and New York reporting.

This makes SALT-focused planning a structural-optimization question, not a marginal-rate comparison.

Once entity-level and SALT-focused considerations are addressed, planning attention typically shifts to individual exposure drivers, particularly how New York evaluates residency and domicile.

New York Residency and Domicile Rules Affecting Individual Tax Planning

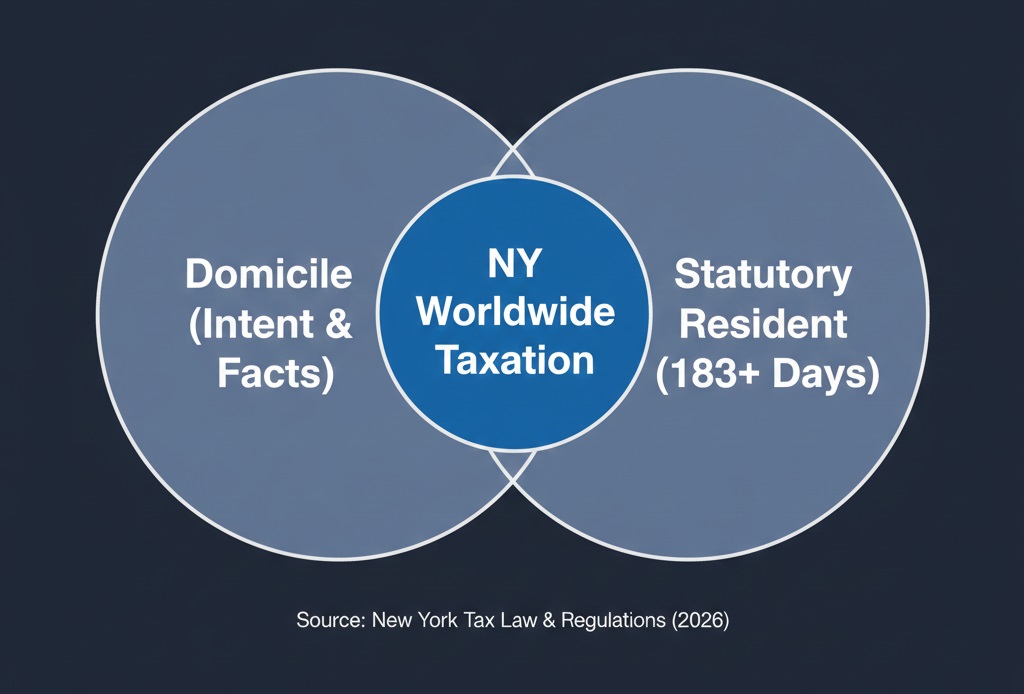

New York evaluates residency using two distinct but related concepts that operate independently of federal residency classifications.

Domicile reflects an individual’s permanent home and intent to return, but New York analyzes domicile using objective facts and patterns (not stated intent alone).

Statutory residency can apply even when domicile is outside New York if the taxpayer

- Maintains a permanent place of abode in New York for substantially all of the taxable year (generally interpreted as more than 11 months) and

- Is physically present in New York for more than 183 days during the tax year (i.e., 184 days or more).

Importantly, “permanent place of abode” is not just a property‑ownership test—auditors and courts often look for a residential connection to the dwelling (facts showing it is maintained as a place of living, not merely held or occasionally available).

From a planning standpoint, these standards require CPAs to analyze documents and behavior over time.

Why Residency Planning Creates Elevated Audit Risk?

Residency determinations attract heightened scrutiny because they depend on objective evidence of living patterns rather than transactional reporting alone.

New York audits commonly examine day-count support and the facts surrounding any claimed permanent place of abode, including whether the taxpayer has a meaningful residential connection to the dwelling.

For CPAs, the primary risk is not arithmetic—it is misclassification, which can retroactively expand the tax base from New York‑source income to worldwide income over multiple years.

Once individual residency exposure is established, planning often shifts to how New York interacts with multi-jurisdictional activity, particularly where businesses and employees operate across state lines.

Multistate and Nexus Considerations for New York Tax Planning

New York creates multistate tax exposure when business activity, employees, or revenue streams cross state lines in ways that meet New York–specific nexus standards.

For CPAs, nexus analysis is not limited to determining filing obligations; it shapes planning decisions related to apportionment, withholding, sales tax collection, and long-term compliance risk.

Unlike federal tax law, which does not rely on nexus thresholds, New York applies its own criteria to determine whether an out-of-state business or individual has sufficient connection to New York to trigger tax obligations.

Because New York frequently acts as a triggering jurisdiction for broader multistate exposure, CPAs often evaluate New York nexus and sourcing issues within a structured state and multistate tax planning framework, rather than assessing New York in isolation.

How New York Nexus Standards Affect Planning

New York evaluates nexus based on economic presence, physical activity, and transactional volume, depending on the tax type involved. From a planning perspective, CPAs must assess:

- Whether business receipts sourced to New York exceed applicable thresholds

- Whether employees, contractors, or agents perform services connected to New York

- Whether recurring activity creates ongoing filing and reporting obligations

Nexus determinations influence more than income tax exposure.

Once nexus exists, New York may require registration, estimated payments, withholding, or sales tax compliance—even if the client has limited in-state activity.

Apportionment and Allocation Rules Impacting New York Filings

When a New York nexus is established, income is not automatically taxed in full. Instead, CPAs must evaluate apportionment and allocation rules that determine how much income is attributed to New York.

These rules rely heavily on receipts-based sourcing, which differs from payroll- or property-based approaches used elsewhere. Planning errors often occur when apportionment is treated as a mechanical calculation rather than a forward-looking risk area tied to business operations and customer location.

Once multistate and nexus exposure is evaluated, planning attention turns to execution risk, including filing timelines, penalties, and enforcement areas that CPAs actively monitor.

New York Tax Compliance Timelines and Risk Areas CPAs Monitor

In New York, compliance risk often arises from missed timelines, misaligned filings, or inconsistent positions across tax types, rather than from incorrect tax calculations. Because New York administers multiple taxes independently, CPAs must monitor overlapping deadlines and enforcement priorities to prevent small timing issues from escalating into material exposure.

Compliance planning in New York is therefore less about reacting at filing time and more about anticipating risk checkpoints throughout the year.

Why Timing Matters More in New York

New York imposes strict filing and payment timelines across income tax, franchise tax, and sales tax regimes. From a CPA perspective, the risk is not limited to late filings—it includes:

- Misaligned estimated tax payments between entity and owner levels

- Late or inconsistent elections that affect downstream reporting

- Sales tax registration or filing delays triggered by the newly established nexus

Because penalties and interest can accrue quickly, timing failures often magnify otherwise manageable tax exposure.

Enforcement and Penalty Exposure

New York enforces compliance through penalties, interest, and audit escalation, particularly when filings indicate inconsistency or omission. CPAs routinely monitor:

- Underpayment penalties tied to estimated taxes

- Interest accrual on late payments, which compounds over time

- Filing discrepancies that increase audit likelihood

Compliance risk increases when information is fragmented across entities, owners, and jurisdictions, making coordination a central planning concern.

Example: Compliance Risk Without a Substantive Tax Error

Consider a business with properly sourced income, correct nexus analysis, and accurate apportionment. No substantive tax position is incorrect. However:

- Estimated payments are made at the owner level, while entity-level obligations are overlooked

- Sales tax filings lag after nexus is established

- Elections affecting reporting are not aligned with filing deadlines

In this scenario, compliance exposure arises solely from timing and coordination failures, not from misinterpretation of tax law.

This is why New York compliance monitoring functions as an independent planning discipline rather than a final filing step.

After compliance timelines and enforcement risks are addressed, CPAs often turn to how structured research and technology support ongoing New York tax planning without replacing professional judgment.

How AI-Assisted Research Supports New York Tax Planning Workflows?

AI-assisted research supports New York tax planning by helping CPAs maintain continuity across complex engagements, where conclusions depend on multiple interrelated state-level determinations made over time.

In New York, planning risk often emerges not from missing a rule, but from losing track of how earlier decisions affect later ones—especially across residency, nexus, and entity-level elections.

This is where structured AI support moves beyond simple research assistance and becomes part of the CPA’s planning control layer.

Why New York Tax Rules Increase Research and Consistency Burden?

New York tax planning frequently spans multiple review cycles, tax types, and client fact patterns. CPAs must ensure that:

- Earlier conclusions remain consistent as client facts evolve

- Planning positions taken for one tax do not contradict another

- Prior-year assumptions are not silently overridden

Without a structured way to track planning logic, risk increases as complexity compounds.

Using AI Tools to Support New York Tax Planning Workflows

Modern AI Tax Tools like CPA Pilot support New York tax planning by acting as a central planning reference point, helping CPAs:

- Maintain continuity of tax positions across residency, nexus, and entity-level decisions

- Revisit prior planning assumptions efficiently when client facts change

- Identify downstream impacts of New York-specific elections or classifications

- Reduce reliance on fragmented notes, emails, and ad hoc research trails

Rather than replacing professional analysis, CPA Pilot helps CPAs retain knowledge within the engagement, which is especially critical in high-risk New York planning environments.

So, don’t wait and book your 30-minute CPA Pilot Demo Today!!!

Frequently Asked Questions on New York Tax Planning

How does New York handle tax planning for trusts and estates?

New York determines trust taxation based on grantor status, trustee location, and source income. A trust may face New York tax even when beneficiaries live outside the state, making trust residency planning critical.

Does New York conformity to federal tax law change year to year?

Yes. New York selectively conforms to federal tax changes. CPAs must review annual decoupling provisions because federal deductions, credits, or exclusions may not apply at the New York level.

How does New York treat carried interest and investment income?

New York taxes carried interest and investment income based on residency and sourcing rules. Special reporting and allocation requirements can apply, especially for hedge fund and private equity structures.

What role does documentation play in New York tax audit defense?

New York audits rely heavily on documentation. Residency logs, work location records, and entity agreements are often decisive, making contemporaneous documentation a core part of New York tax planning.

Can New York tax planning affect estimated tax payment strategies?

Yes. New York estimated tax requirements differ from federal rules and may be impacted by residency changes, entity elections, or credit timing, requiring separate state-level cash flow planning.